WHAT DOES A BOOK COST?

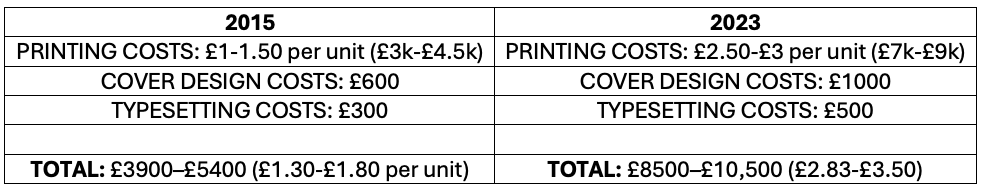

COSTINGS AND PROFIT MARGINS, 2015 and 2023

BACK IN 2015 (pre-Brexit!) – and partly in response to a social media post which asked what an earth publishers (small and large alike) were doing with all the money they were taking home on their book sales – Galley Beggar Press published a break-down of (i) the production costs of a ‘typical’ book, and (ii) the sort of profit margins that this typical book, and print run, might see.

This April (and again, in response to something: this time a meeting Sam Jordison – co-director at Galley Beggar – had at Westminster, to talk about some of the issues small presses are facing), we thought we might try out those calculations again.

What emerged – as we realised it would (experiencing everyday the challenges of the current climate) – was much starker even than we were expecting.

… Anyway. We thought you might like to see these calculations too. And we should say right here that they’re personal – based on general knowledge of the trade and also (a bit more definite: the numbers don’t lie), the bills, estimates, and cash-flow sums that we deal with every year, month, week.

It’s one bird’s eye view – but hopefully a useful one, and hopefully one which tells you just how up against it many (most) of our small presses and even mid-sized publishers are; as well as how much your help and support is needed, and how much needs to change.

This is an industry – an immensely valuable one, brimming with passion and care – that is running on borrowed time.

1. the first bit: PRODUCTION

The following information is based on a book with the following specifications:

RRP: £8.99 (2015) and £10.99 (2023)

TYPICAL PRINT RUN: 3000

PAGE EXTENT: 300–500 pages

* Two things to note: (i) these costings are based on a 3000 print run; as around 40% of the costing is the initial set up, unit costs go down the more copies you print (e.g., in 2014, after our second title, A Girl Is A Half-formed Thing, won the Women’s Prize, the unit cost was c. 0.47 for a 27,000 print run; in 2023, an 11,000 print run of our Booker Prize-longlisted title After Sappho was c. £1.73 per unit); (ii) ordering a very high print run to bring down the unit price is a limited option for smaller publishers and also literary imprints of even the bigger publishers, as the median sell-through for literary fiction (in the first year of publication) is 241 copies (Publishers Association stats).

2. the middle bit: POST-PRODUCTION DISTRIBUTION AND BOOKSELLER DISCOUNTS

Selling to bookshops

When you sell into a bookshop, the bookseller (and of course wholesale distributors such as Gardners) will need to ask for a discount.

Chains. For the ‘big booksellers’ and chains, this will range according to the publisher and the amount that they buy in (in our experience, Waterstones, Foyles and Blackwells, for instance, do take into account the size of a publisher and its capacity for discounting). For orders of a book of under 400 units, the discount will be roughly 50–55%. For much larger orders (which would require a larger print run and is thus not directly relevant to the above figures – with larger print runs, the unit cost comes down), the discount might be anything from 60–68%. (We were once asked, by an online bookseller that has since gone under, for a 90% discount on a bulk order.) WH Smith, who we no longer work directly with, and in addition to a large discount, used to (and may still) ask for a ‘retro’ bonus for every copy sold: this could be anything from 35–70 pence.

Independents. Independent booksellers and shops generally either buy in from Gardners (above) or ask for a lower discount of c. 40%.

This is on a sale-or-return basis, which means that if a bookseller doesn’t sell a book, they can return it. It is something that was introduced in the mid-twentieth century and (while it’s something that booksellers need: they are also up against huge challenges in the current climate) the only industry we are aware of that has this system. Booksellers try to stick to a 5–10% return rate.

Distribution

A distributor is someone that most mid-sized and smaller publishers (the ‘Big 5’ largely have their own) partner with and pay to sell books into bookshops. Distributors offer a variety of services (and at different price points), but – for distribution that includes (i) repping (a team of also representatives who travel to bookshops all over the country, presenting your books), (ii) negotiating deals, and (iii) fulfilling bookshop orders (as well as warehousing the books themselves) – the cost will generally come to around 25% of monthly sales.

3. tHE SUMS

OK, so what does this all add up to?

Here’s one example:

If a bigger bookseller buys in 600 of your titles (£8.99 RRP in 2015, £10.99 in 2023), using a 50% bookseller discount, in 2015 the publisher will be paid £2697; in 2023, £3297.

So £4.49 and £5.49, respectively.

… An increase! (Thanks, bookshops!)

Or – it would be an increase, without considering the other factors.

Let’s break it down.

So, the author – who, after all, wrote the brilliant book – needs a royalty. This is generally priced on an escalator, and might look like 10% up to 3000 copies; 12.5 after that (up to 5000 copies); and 15% after that (5000 and over). (NB: This is based on Galley Beggar contracts, on a net basis, and higher than the industry standard – and we’d love for it to be higher still. We are writers ourselves, as well as publishers…)

So, after the royalty payment, you have: £4.04 per unit (2015) and £4.94 per unit (2023).

There’s the 25% distribution fee as well, which leaves: £2.92 per unit (2015) and £3.57 per unit (2023).

Oh wait! We haven’t included returns. Let’s be generous, and say a 7.5 return rate, instead of a higher 10% – and we’ll have: £2.23 per unit (2015) and £3.04 (2023).

…

OK! So finally, let’s take off the actual cost of producing the book itself: £1.30–£1.80 in 2015 and £2.83–£3.50 in 2023.

That leaves us with, in 2015: £0.43–0.93; and in 2023: £–0.46–£0.21.

Profit margins haven’t just halved – they’ve plummeted.

(Also: £–0.46-0.21 – to cover in-house wages, rents, energy, marketing, travel, tax… It’s… challenging…)

3. WHAT DOES IT ALL MEAN?

Well, it makes things hard. It makes us angry about some things (hi, Brexit, thanks for that), determined about others – and also grateful in all sorts of ways. We survive thanks in large part to our wonderful subscribers, a huge amount of support from booksellers, and the people who buy direct from this website. We’ve also been very lucky to have had authors who have broken through, got onto prizes, sold foreign rights and won enough attention to make some of those margins a bit easier. We have had very good readers – and that makes it all worth while. We also have hope and belief in the future. Here in Britain, the political winds are starting to blow in a better direction and we’re reasonably optimistic about future stability – and maybe even meaningful support. We also continue to believe absolutely in the power and importance of literature. These books matter and we owe it to the world to continue to bring them out… even if we sometimes worry about the payback (and even, sometimes, survival).

Two very final things:

If you’re reading this, and wondering what you can do to help, the very easiest thing is to go out and buy a book from a small (but mighty) press today. Many smaller presses have shops on their websites (And Other Stories, Bluemoose, Dead Ink, Influx, Peepel Tree, to name just a few). And if you buy from them directly, there’ll be fewer cuts and more money for the coffers. (But! Bookshops need support as well – it’s a hard world out there – so maybe divide the love and do that, too.) For Galley Beggar Press, you can become a subscriber (our subscription programme is something we quite literally would not survive without); take a look around our shop at some of our amazing, and prize-winning, writers; or (a huge help!) pre-order some of the truly brilliant books we have coming up, from the new Christmas Pocket Ghosts range, to debut writers Noémi Kiss-Deáki’s Mary and the Rabbit Dream and Mark Bowles’s All My Precious Madness, to the phenomenal Alex Pheby’s Waterblack.

If you’re a small or mid-sized publisher and have your own figures and points to add, please drop us a line! We’re very interested to know how our numbers tally with yours, what we’ve missed out, what we’ve downplayed (or overplayed) – as well as hearing about additional problems, and potential solutions. (If we get enough responses, we’ll add a further section to the article.) Most of all: La lutte continue! We salute you.